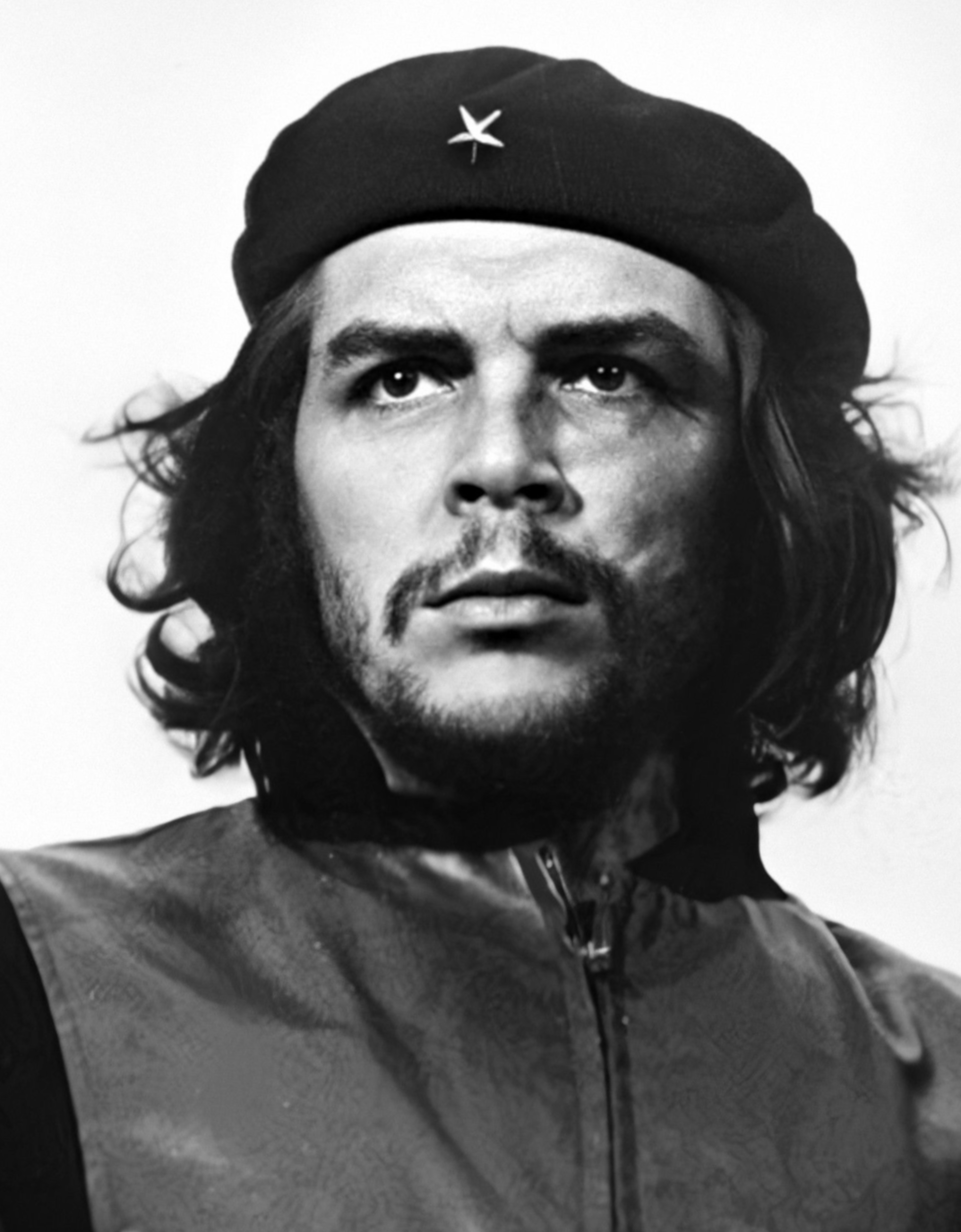

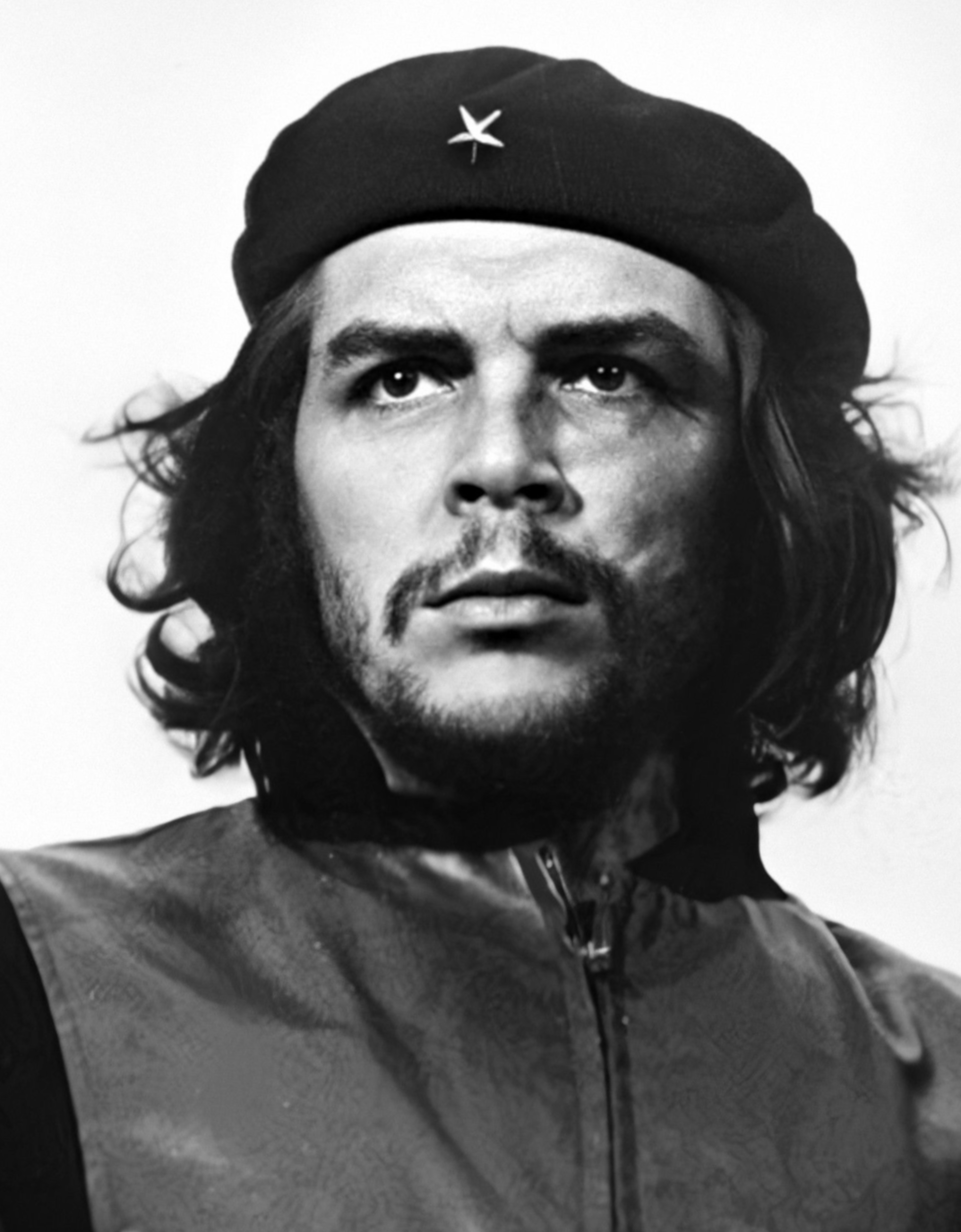

Like others, I imagine, I knew the name from the image on the poster and t-shirts —

but I knew very little about the man. Anderson (http://www.newyorker.com/contributors/jon-lee-anderson), who seems to be something of an expert on this topic (he was one of the first people called when – spoiler alert – Che’s body was found) has compiled a remarkably compelling story of a man, devoted to his mother and his country and seriously troubled by asthma, who tried to live according to his ideals and, sometimes brutally, tried to persuade others to do so as well.

I was struck by two aspects of Che, the young man. First, his travel. He was passionate about and privileged to be able to see a great deal of Latin America as a young man, though he did not travel in anything resembling a comfortable way. He also read – voraciously.

Anderson’s account of ideological development, his friendships, and his introduction to Fidel are riveting. Yet, he also knows when to stop, offer an asterisk, and write ‘see notes for more.’ The account of the Cuban Revolution brings you right there. Anderson’s tone is spot on. He offers his insights into Che’s perception of people and the big enemy, the United States, not in a detached fashion, but a reasonable one. Che’s real issue, it seemed to me, was with colonization.

Tellingly, the book bogs down when Che does. The Revolution, having been won, is know about details. Che digs in, but he seems to be a restless soul. It reminded me of the end of the Robert Redford movie The Candidate, Redford’s character, having surprisingly won an election, escapes the chaos of the celebration and earnestly asks his advisor, “What do I do now?”

Anderson’s work on Che’s efforts in the Congo and in Bolivia are harder to track, perhaps, as he points out, because the number of sources narrows. Still, this is a portrait of man who, until the end, tries to match his vision to his life, and I found, though I wanted to offer him advice at times (is there really a revolutionary formula?), I had to admire. I understood his rejection of the political process and wonder about it even in our days.